1. Woodstock’s organizers originally wanted to build a studio, not host a concert.

In fact, only one of the four men who threw the party of the century had any experience helming a music festival. Earlier that year, Florida-based promoter Michael Lang had organized a concert in Miami that drew 40,000—the largest concert in history up to that time. Lang’s friend Artie Kornfeld worked for Capitol Records, but had never worked on anything the size of Woodstock. Their partners had even less experience. John Roberts and Joel Rosenman were the Ivy League-educated sons of wealthy businessmen, and Roberts was the heir to a pharmaceutical fortune. The group came together when Roberts and Rosenman, looking for investment opportunities, agreed to back Lang and Kornfeld’s idea for a recording studio in Woodstock, New York, a popular arts community in New York’s Ulster County that was home to musicians Bob Dylan, The Band, Jimi Hendrix and others. The four men soon abandoned plans for the studio, however, and instead decided to throw a large, outdoor, rock festival. They kept the Woodstock name because of its connection to Bob Dylan, though Dylan himself never played at the festival.

2. The festival actually took place nearly 70 miles from Woodstock in Bethel, New York.

Unable to find a suitable spot in Woodstock itself, the organizers signed a deal to hold the festival in an industrial park in nearby Wallkill. However, when local officials began to realize that the festival was expected to draw 50,000 people, they balked and just a month before the concert passed a law prohibiting the event. The organizers were then approached by Elliott Tiber, a motel owner from Bethel, New York, who offered the use of his farm, which was quickly deemed too small. Tiber, however, introduced them to his friend Max Yasgur, who finally agreed to lease them 600 acres of his sprawling alfalfa farm for $75,000. With estimates of the crowd size now surging well past 50,000, Yasgur faced increasing pressure from local residents and the business community to cancel, but refused to renege on the deal he had made with the Woodstock organizers.

3. Richie Havens was not meant to be the first performer.

With Sweetwater, the concert’s first scheduled performer still stuck in traffic, organizers scrambled to find a replacement, finally selecting folk singer Richie Havens. Havens started his set at just after 5 p.m. on Friday afternoon, and by some accounts continued playing for nearly three hours. Every time he tried to leave the stage, organizers convinced him to keep playing, as they still hadn’t rounded up the next act. When Havens began to exhaust his repertoire, he threw in a few Beatles covers, before finally improvising a new song, “Freedom,” on the spot to close out his epic set. Havens was finally allowed to leave the stage after a U.S. Army helicopter, chartered by the organizers, arrived with additional performers aboard.

4. The music nearly came to a halt on Saturday night.

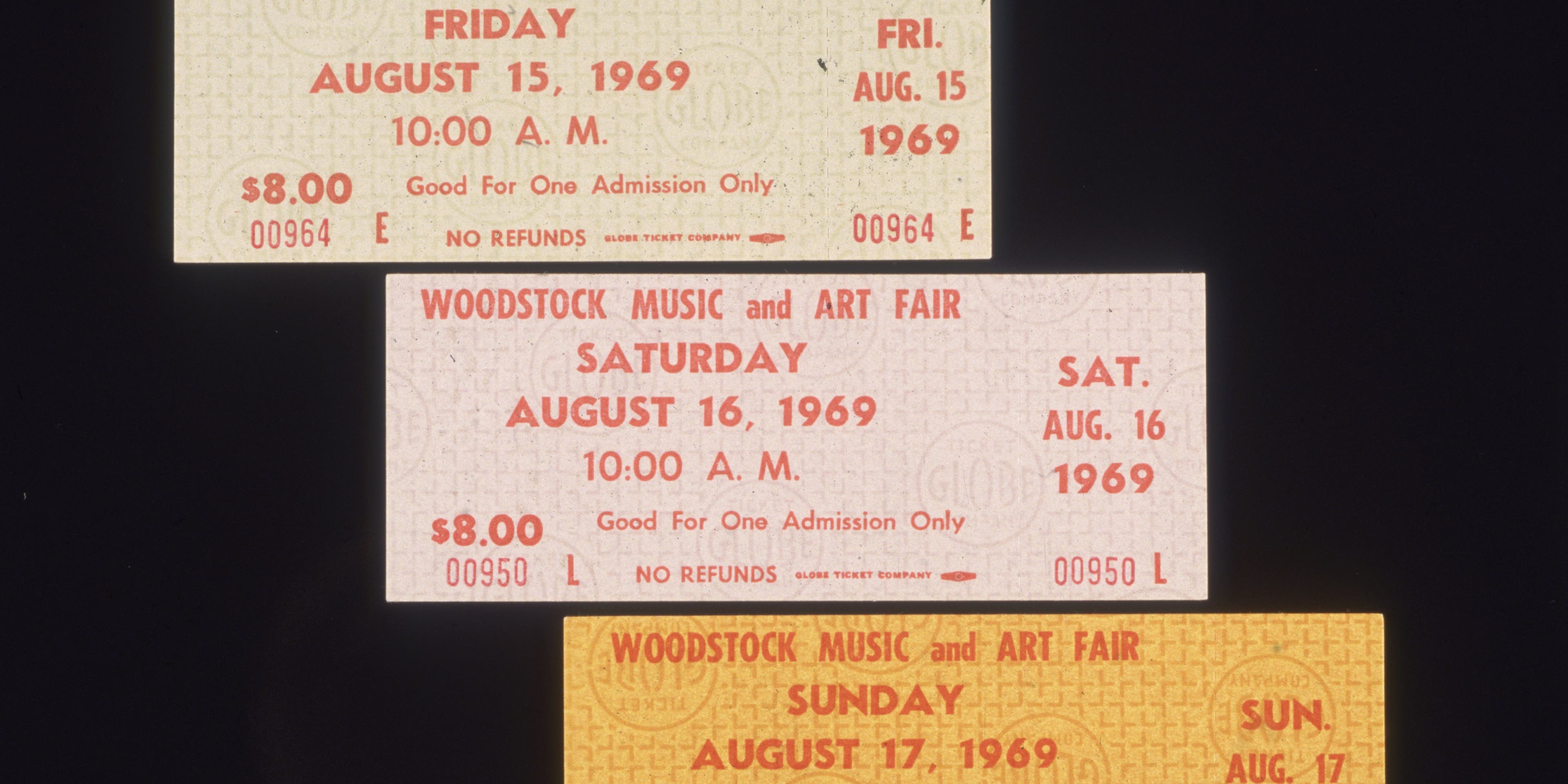

Just hours into the festival, Woodstock’s organizers were hemorrhaging money. The sheer number of attendees and the logistics of collecting money and tickets at the gates had forced them to abandon the idea of a for-pay concert and instead let everyone in for free. In addition, they were forced to spend tens of thousands of dollars contracting helicopters to transport food, supplies and the musical acts to and from the site. Weeks earlier, in an effort to attract music’s biggest stars to the festival, Woodstock’s organizers had agreed to pay some artists more than twice their going rate—and on Saturday many of them demanded that they be paid, in cash, before going on stage. Fearful of what the crowd would do if the music came to a halt, organizer John Roberts agreed to use his trust fund as collateral for an emergency loan. Organizers finally convinced the manager of a local bank to open up close to midnight on Saturday to get them the funds.

5. Jimi Hendrix was the headliner at Woodstock, but few people actually saw him perform.

Hendrix was one of those artists who demanded his fee, nearly $200,000 in today’s money, in advance. He spent much of the weekend wandering around the festival grounds, despite the fact that he was scheduled to be the final performer. By Sunday, it was clear that the announced schedule had gone off the rails, with acts finally appearing hours after their intended start times. However, due to a clause in Hendrix’s contract that stipulated that no act could perform after him, organizers were unable to move him to a Sunday evening slot. By the time Hendrix took the stage at 9 a.m. Monday morning, most of the festivalgoers had headed home, and missed Hendrix’s set, including his legendary rendition of "The Star-Spangled Banner."

6. Martin Scorsese cut his chops working on the Woodstock documentary.

Just days before Woodstock began, organizer Artie Kornfeld struck a deal with Warner Bros. Studio to film the festival for possible release as documentary film. Director Michael Wadleigh, hastily assembled a crew, including future award-winning director Martin Scorsese, a recent New York University film graduate with only a handful of credits to his name. Over the course of three days, Wadleigh and his crew shot over 120 miles of footage, which Scorsese and others eventually edited down to three hours for release. The film went on to win an Academy Award and became one of the most profitable films of all-time, but Kornfeld’s deal, which gave financial control to Warner Bros., meant Wadleigh and Scorsese received little money.

7. The most famous song about Woodstock was written by someone who wasn’t even there.

At the insistence of her then-manager David Geffen, Canadian singer Joni Mitchell had been booked to appear on the popular Dick Cavett Show on the Tuesday after Woodstock. Geffen, fearful that Mitchell would be unable to make it back to New York in time, refused to allow her to attend the concert. Mitchell had to settle for watching the events unfold on television. Mitchell made it to the Dick Cavett show, but so did several other artists who had traveled up to Yasgur’s farm, including Jefferson Airplane and the newly formed rock super group Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young (who had made one of their first public appearances at the concert). Band member Graham Nash, Mitchell’s boyfriend at the time, vividly described the weekend’s events, leading Mitchell to pen a new song, “Woodstock,” which even many attendees felt perfectly captured the experiences of those who had attended the event.

8. There were three deaths at Woodstock, but no confirmed births.

Three young men died while attending Woodstock, two from drug overdoses and another–just 17 years old—was run over by a tractor collecting debris while he was asleep in a sleeping bag. For decades, rumors have swirled that several women gave birth while at the festival. No births were recorded at the site itself, but eight miscarriages were. When the festival was finally over, the New York State Department of Health recorded 5,162 medical cases over the nearly four days, 800 of which were drug-related.

9. That weekend, Bethel was the third largest city in New York State.

Feeding nearly 500,000 people was a logistical nightmare. Members of the Hog Farm, a New Mexico-based commune initially hired to help keep the peace, quickly switched gears, recruiting new (temporary) members on the spot to help cook and serve to the masses. When a local Jewish Community Center heard about the food shortages, they too sprung into action, supplying thousands of sandwiches that were eventually flown into the area from a nearby air force base.

10. It took a decade for the Woodstock organizers to turn a profit.

All told, Roberts, Rosenman, Lang and Kornfeld spent nearly $3.1 million ($15 million in today’s money) on Woodstock—and took in just $1.8 million. Roberts’ wealthy family agreed to temporarily cover the enormous costs, providing they were repaid, but it wasn’t until the early 1980s that Rosenman and Roberts were finally able to pay off the last of their debt.